In the 1970s the U.S. economy was prospering from the Greatest Generation’s return from winning World War 2. Their progeny, the Baby Boomers, were fast becoming the luckiest generation. Many industries were benefiting from a little-known fact: The number of homes built in the 1970s would surpass any other decade before or after. And those houses needed furniture.

The first 30 Years

The golden age of furniture making in the U.S. ran from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s. Annual manufacturers’ shipments of wood and upholstered products grew from $4.5 billion in 1970 to $16.3 billion 24 years later. The wood/upholstery mix was about 60/40. In 1985 the 400 largest of 2,500 firms produced 80 percent of shipments. Only 19 companies had annual sales greater than $100 million. Industry net profit after taxes averaged 4 percent.

Production of wood furniture designs most demanded by U.S. consumers is labor intensive. Much of the labor is difficult, if not impossible, to replace with capital investment. Factory labor including benefits ranges between 25 and 30 percent of manufacturer’s selling price. North Carolina furniture workers were paid $7.20 per hour in 1987, $9.75 in 1995, and $13.00 in 2005.

The typical furniture factory of the 80s and 90s featured numerous manual machining, assembly, and finishing operations with a few islands of automation. Computerized information systems for managing production were virtually non-existent. Compliance with tighter safety and environmental regulations consumed an increasing share of capital available for capacity expansion and productivity improvement. As a result many plants were obsolescent.

Foreign competition

Importing offered U.S. furniture makers the opportunity to manufacture in countries with low wage rates using suppliers’ plants. In the early 1970s Canada and what was then Yugoslavia were the top sources for U.S. customers. By 1978 Taiwan had become the largest supplier and remained a dominant member of the country rankings through 1994.

By the early 1990s Taiwan had developed industries that manufacture higher-value products than furniture. Wages there rose to 35 percent of rates paid for comparable work in the U.S. More importantly the Taiwanese wage was seven times the rate paid Chinese factory workers. That fact proved to be the critical impetus for the relocation of Taiwanese factories to China. There the factory owners found three key factors for success:

- Productive Labor: Combining the native productivity with the mainland’s low wage rates yielded a hyper-competitive cost. The result was a labor content of about 5 percent of selling price versus 25 percent in U.S.-made furniture.

- Low Cost of Entry: The cost of building furniture making capacity was about two-thirds lower than in the U.S.

- Government Incentives: Factory owners benefited from incentives for job creation and rebates of value-added taxes on export sales.

Other contributors to the amazing growth of China were inexpensive ocean freight and a fixed currency exchange rate from 1995 through 2005.

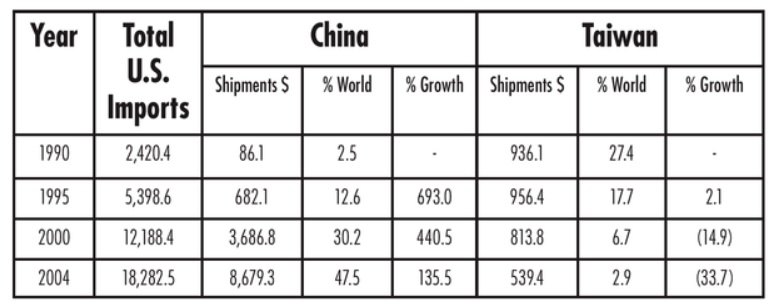

The tidal wave of price competitive, design-rich imported furniture was forming. In 1995 China exploded as a furniture source. Producers there combined to rank third among supplier countries with a nearly 13 percent share of imports. By 2004 China supplied US$8.68 billion of furniture products garnering a 48 percent share of imports.

Since the turn of the century more than 300 wood furniture plants have been shuttered in the U.S. Only a few U.S. companies now operate a single domestic wood plant. Even fewer run multiple factories. Of course the workers in those closed factories were harmed. From 1999 through 2010 about 40,000 furniture jobs were lost not including those in the furniture supply chain.

The most painful result has been the rending of the social fabric of small town America where few other employment opportunities exist. As a result two and three generations of families in those communities have had no working breadwinner. The U.S. consumer now pays less for furniture, but no one can measure the human cost.

China today

By 2017 Chinese furniture makers had captured 58 percent of U.S. furniture imports with US$16.6 billion of shipments to the U.S. A similar dominance is being achieved not only in sectors requiring low- and medium-skilled labor like apparel and furniture but in high-tech products like sophisticated electronics and smart phones. Its economy is no longer dependent on unskilled labor but now competes in product sectors requiring innovation.

Like Taiwan the transition to higher-value products has brought higher wages. China mandated a series of annual wage increases averaging 15 percent. According to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) fully-loaded wages are now within five to seven percent of those in the southern U.S. Wages are also rising due to its declining population growth. No doubt Chinese furniture companies are finding tougher sledding in some export markets as customers shift to suppliers in Vietnam and other countries with lower wage rates.

China is fast replacing its export economy with one driven by consumers. Many export-based companies are now focusing their resources on the burgeoning domestic market as the economy consumes more of what it produces.

Consultants like McKinsey and BCG plus publications such as The Economist claim that the advantages of globalization are fading. That phenomenon – the cross border integration of companies to utilize each country’s comparative advantages -- created today’s China. These experts assert that the differential between the fully-loaded costs of an imported and domestically-produced good is no longer as compelling. One result has been a boomlet in reshoring production to the U.S. in certain industries but not furniture.

Does that opinion put to question the continuing viability of China as a furniture supplier? Many factors say no:

- Ample Labor Resources: Factories are moving to the under-utilized interior away from the higher-cost coastal region.

- Well-Developed Supply Chains: Vertically-integrated value chains enable efficient production.

- World-Class Logistics: Efficient land/ocean transport and port facilities ensure quick, inexpensive delivery to customers.

- Productivity Opportunities: Factories can lower labor content through targeted capital investments that streamline manufacturing.

Bottom Line

The economic nature of things virtually ensures that tomorrow will be different than yesterday. On that basis China will eventually lose its competitive advantages. But until jobs are created for the millions there who remain under-employed, that event will be later rather than sooner. And don’t forget that the shipments to the U.S. by the next nine largest source countries is just under 61 percent of China’s.

Have something to say? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.