Two shops bid on the same plane-Jane kitchen. One shop owner in Pennsylvania says it’s a $4,500 job. Next door in New Jersey, a shop says, oh no, $32,000 is closer to the right price. Not to be outdone, another New Jersey shop takes the same bidding specs, sharpens their pencils and comes up with a $25,000 price. The New Hampshire shop that actually did the job had it priced at $12,500. Can the highest bid really be seven times what the lowest bid is? What’s going on?

Actually nothing unusual at all.

These are some of the results from the 2017 FDMC Pricing Survey that show huge variances in price on bids for the same work. They reflect the same kinds of wide variances consumers face when requesting bids for custom woodwork. Based on real jobs done by real shops, the survey makes original bidding specifications available to shops all across the country, asking them to price the projects as if they were bidding on the jobs in their own shops. The results show not only wide variances in total price, but also striking differences in breakdowns for materials, construction hours, finishing and installation.

Even with decades of business experience under the belts, as many of the Pricing Survey bidding shops have, they clearly still struggle with pricing custom work and managing all of the variables. There are as many pricing systems as there are shops, and the numbers they come up with reflect that. Complexity of the process leads to errors and miscalculations, but few shops have figured out how to fine-tune the process.

Even when they come up with clearly questionable numbers, they are reluctant to make adjustments. For example, one experienced estimator in the survey was confronted with materials numbers that clearly were inadequate and would likely lead to bad bids, such as $163 in materials cost for an entire kitchen. The estimator’s response was that the low number is what came out of the spreadsheet program the shop uses. We bet lots of shops would be able to bid low on a kitchen project if they actually could buy all the materials for under $200!

Similar wackiness shows up when you look at time estimates. Even on a low-hours project such as a custom contemporary coffee table, the numbers are all over the map. The original maker of the project said their shop had 32 construction hours in making the table. But other shops estimated anywhere from a low of 20 to a high of 68. Still, the average came in remarkably close to the actual hours at 34.

So, what accounts for the huge span in numbers? Clearly, there are shops with high overhead and low overhead. And they are located in diverse areas that likely cater to higher or lower price clientele. Some shops are more automated than others. Some have more experience than others. But none of those factors consistently correlates with the bids.

Shop rates probably come the closest to correlating to high and low bids, but even that measure doesn’t work. In the most popular project in this year’s survey, a home library, the second and third lowest bids came from shops with above average shop rates. The shop with the highest shop rate ($145 per hour) actually bid thousands less on the project than the high bidder with a shop rate 50 percent lower at $95 per hour.

So, if the numbers vary so widely without consistent correlation, you might well ask what value does the survey have? To start to find an answer, go back to that estimator with the spreadsheet that gave such low materials numbers. By seeing the results of the survey, the estimator got a big reality check and will take another look at the shop’s estimating procedures and calculations.

Similarly, you can study the survey results and compare them to how you would price the same jobs. If you haven’t already, you can download the same bid package used by all the bidders to see the exact specifications they went by to arrive at their bids (link). Pay close attention to calculations for materials and time, numbers that seem to especially vex many shops when figuring the cost of work. Take a look at your shop rate and see how it compares. When’s the last time you actually figured your loaded hourly rate based on current overhead costs? Maybe it’s time to take it up a notch.

Finally, put yourself in your customers’ shoes. What would you think if you were faced with bids from competing shops that varied as much as these do? How could you choose the best shop to do your work? Is the lowest bid a real deal or a huge mistake that will show up later? Is the highest bid a reflection of really premium work or just a bloated price that will help the shop owner make his next boat payment?

Now, look at it from your side of the desk. Are you low-balling prices to get work in a market that actually will pay a lot more? Are you routinely screwing up estimates by not keeping track of real materials and labor costs? Are you sure your prices always account for costs, including all of your overhead, and still give you a fair profit margin? Are you content to bid jobs with just a tape measure when we know today’s custom cabinetry is lots more complex than some average price per foot?

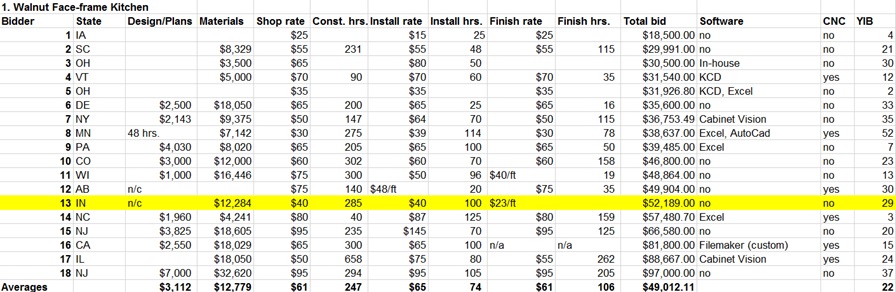

Walnut Face-Frame Kitchen

Walnut Face-Frame Kitchen

The Project: This beaded inset walnut face-frame kitchen has a lot of distinctive details, especially the custom hood over the stove, applied raised panels on appliances and on exposed ends, carved elements, architectural components, and two kitchen islands.

Analysis: The most complex project of this year’s survey actually attracted closer bidding than some of the more simpler projects. Still, the high bid of $97,000 was more than five times the low bid of $18,500. The original maker’s bid of $52,189 was just a few thousand dollars higher than the $49,012 average bid. In this project there seemed to be no correlation between experience, CNC, software, or region and price. Variance factor: 5.24

Analysis: The most complex project of this year’s survey actually attracted closer bidding than some of the more simpler projects. Still, the high bid of $97,000 was more than five times the low bid of $18,500. The original maker’s bid of $52,189 was just a few thousand dollars higher than the $49,012 average bid. In this project there seemed to be no correlation between experience, CNC, software, or region and price. Variance factor: 5.24

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"97331","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"480","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"360"}}]]

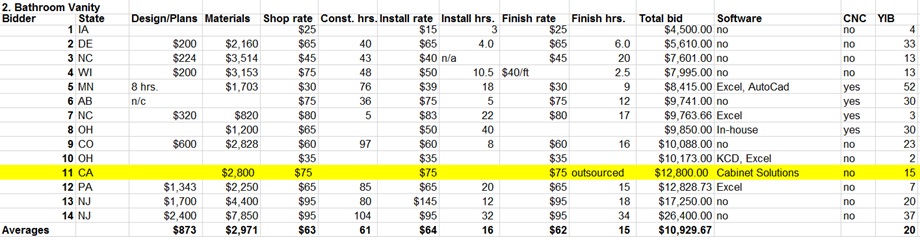

Bathroom Vanity

The Project: This elegant furniture-style bathroom vanity was fabricated in African mahogany. Interior cases were done in prefinished maple. All drawers are solid hard maple with dovetailed construction and Tandem slides. The finish is a dye stain with conversion varnish clear coat.

Analysis: This project had a strikingly high bid ($26,400) and a strikingly low bid ($4,500). If you drop those bids, than the variance factor also drops significantly, but it still means the highest bid would be more than double the lowest bid. Shop rates seem to have little correlation with final price as some of the higher shop rates of $75 and $80 per hour show up in the lower third of the bids. Similarly, more experienced shops show up at both ends of the spectrum. Interestingly, the CNC shops are all clustered together just below the average bid. Variance factor: 5.87

Analysis: This project had a strikingly high bid ($26,400) and a strikingly low bid ($4,500). If you drop those bids, than the variance factor also drops significantly, but it still means the highest bid would be more than double the lowest bid. Shop rates seem to have little correlation with final price as some of the higher shop rates of $75 and $80 per hour show up in the lower third of the bids. Similarly, more experienced shops show up at both ends of the spectrum. Interestingly, the CNC shops are all clustered together just below the average bid. Variance factor: 5.87

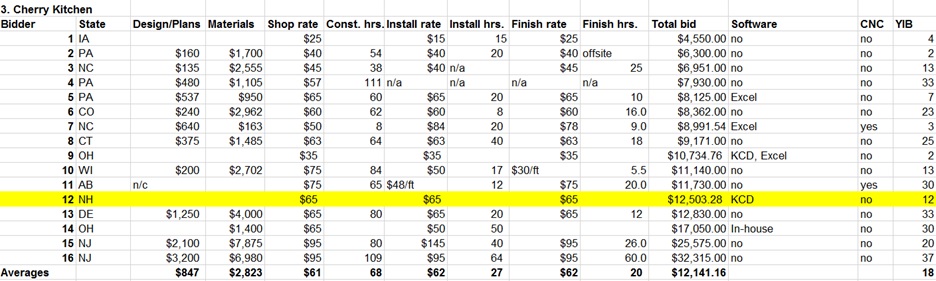

Cherry Kitchen

The Project: This cherry kitchen features a U-shaped design with square flat-panel doors and drawer fronts. There is a lazy susan in one base cabinet and 235 inches of 2-3/16-inch crown moulding. Solid surface countertops complete the project.

Analysis: his project shows that a relatively simple and straightforward project does not necessarily lead to closer bidding. The high bid of $32,315 is more than seven times the low bid of just $4,550. The original maker’s price of $12,503 is pretty close to the average bid of $12,141. It’s interesting that the top two bids both came from New Jersey shops that report the same $95 shop rate. However, there’s still more than $6,700 between their bids, a difference that is more than the two lowest total bids from shops in Iowa and Pennsylvania.

Variance factor: 7.10

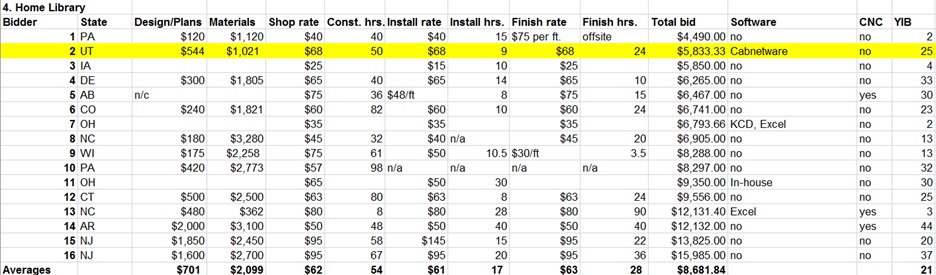

Home Library

This residential library project was done for a showcase home in a Parade of Homes project. It features knotty alder woodwork with square, raised-panel doors. The finish is a custom stain with glaze. Other details include 4-inch crown moulding with base and rope moulding, small pewter knobs, 96-inch build height, raised panel finished ends, and a wood top.

Analysis: The most closely priced project in this year’s survey, this residential library still garnered a high bid ($15,985) that was three and a half times the low bid of $4,490. Construction hours estimates averaged 55, very close to the 50 reported by the original maker. But materials estimates ranged widely, with the average more than double the original maker’s materials number. Another huge variance comes in the installation time estimates, which range from a low of just 8 hours to a high of 40, and finishing, which ranges from 3.5 to 90 hours. Variance factor: 3.56

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"97337","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"477","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"480"}}]]

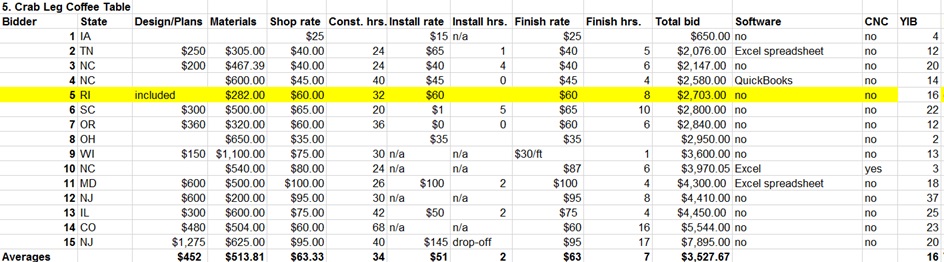

Crab Leg Coffee Table

The Project: This elegant coffee table is made with bird’s-eye maple veneer in the top with mahogany legs and frame and wenge corner splices. The top is two layers of 5/8-inch MDF laminated to make a 1- 1/4-inch core, which was vacuum veneered with the maple. The table is spray finished with waterborne lacquer. Finished measurements are 48 x 22 x 18 inches.

Analysis: This deceptively simple project attracted by far the widest range of pricing in this year’s survey. The high bid of $7,895 was more than 12 times the low bid of just $650. The original maker priced the piece at $2,703, still well below the average bid of more than $3,500. Perhaps due to the small size of the project, time and materials numbers were closer on this than other projects in the survey. Average construction hours at 34 nearly matched the original maker’s 32 hours, but the average materials cost of more than $500 was 82 percent higher than the original maker’s quote of $282. Variance factor: 12.15

Have something to say? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.