Q. We are a fairly small shop and have an issue. It seems to me that when we buy a piece of upper grade lumber that is curved sideways, end to end, we get a lower yield and so should not pay as much. Can you agree?

A. You are indeed correct. The defect is called sidebend, sweep or crook. Those are all the same thing, but different names.

The rules for grading hardwood lumber do indeed penalize a piece that has sidebend.

Lumber is graded based on the clear area.

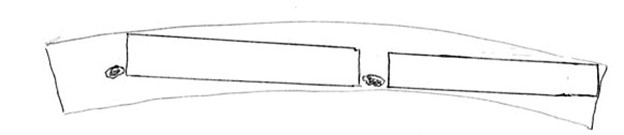

However, these rectangular clear areas must all be on the same axis, as shown in the sketch; that is, they cannot curve around the piece with sidebend.

The clear areas can be different lengths and widths, as dictated by the rules.

In the sketch, consider this mostly clear piece of lumber.

The black circles are two knots. Although straight when sawn, after drying it has sidebend.

Before drying, this piece was likely very useful and graded as FAS with one large clear rectangular area.

With sidebend, however, the rectangular clear areas cannot curve around, so their area is quite limited.

This piece might grade only No.2 Common.

There is one small possible issue. A few — very few — people sell lumber based on the grade when the piece was green (that is, before it dries and shrinkage and warp take place).

It was graded green (before any drying), so the piece was straight.

After drying, the lumber was not regraded, so the green grade is controlling.

With shrinkage and warp, this is indeed not favorable for a purchaser like you.

So, it is indeed common practice to regrade the lumber after drying, in which case warp, checks, splits, and other defects are considered.

Q. I read an article that you wrote suggesting that taking 30 moisture readings on incoming lumber helps characterize the moisture content for the load. If we have 6,000 BF of 4/4 and 6,000 BF of 5/4, to properly sample this load, would we take 30 random samples of the 4/4 and 30 random samples of the 5/4?

A. Thanks for your note about sampling lumber. I think I did not write this clearly enough in my original response. Let me try again.

You could take two readings (of normal pieces of lumber and not the end or top layer, etc.), average the two readings, and come up with an estimate of the MC of a load of lumber.

However, I think you can appreciate that this estimate would not be very accurate, or maybe we should say reliable.

To get a very reliable number, we need somewhere around 30 readings.

In some cases, where there is little variation (1/2% MC or less) from one reading to another, maybe 10 to 15 readings will be adequate.

That is, if we do not see any pieces that are close to the upper limit of acceptable MC after 15 samples, we can probably determine (it is all about probability if we do not measure every piece) that the lumber is okay.

IMPORTANT POINT #1: The only way you know for 100% certain that the MC is okay in a load is by measuring every piece.

In-line moisture meters that do take MC readings of every piece are quite expensive, so we use the random sampling, probability technique to save money.

IMPORTANT POINT #2. We also need to ask ourselves, “How critical is it if the lumber has a few pieces that are too wet, too dry, or both?” and “How critical is it for the MC of every piece to be right on target?”

I will add that in 40 years of this work, I have seen many times that when the average MC is on target and there is little plus or minus variation, there will be dramatically fewer machining and gluing issues and few calls, such as warping complaints, from customers.

I appreciate that it is not trivial to measure 20 or 30 pieces of lumber, although using a pinless meter, that you have calibrated specifically for yourself using the MC readings from a pin meter, make measuring very quick, accurate and somewhat easy.

So, you have to weigh the cost of sampling the incoming MC against the cost of having and fixing moisture-related defects.

MIXED THICKNESSES. If I were running a kiln with both 4/4 and 5/4 lumber, there is a risk that the 4/4 is a bit too dry and/or the 5/4 is a bit too wet unless special equalization is used.

So, you need to separate samples when buying different thicknesses of lumber.

However, if I sample the 4/4 and it is okay, then I would sample 10 random 5/4 pieces.

If the average of 10 pieces agrees with the 4/4, then I would feel some confidence that the 5/4 is okay too.

SAVING TIME. In fact, once you determine that a certain supplier seems to be on target and his kiln operator is running the kilns well, I would sample 10 pieces, and if the average of 10 looks really good, then I would assume that this is another good load from that supplier.

Do you have a community college nearby or maybe Cooperative Extension county office?

If so, see if there is a STATISTICS expert on “ACCEPTANCE SAMPLING” who can develop some further practical techniques. Does all this make sense?

Let me know if you have questions.

Q. I just read an article talking about the effect of drought and increased sea level on the salt in rivers and the trees around them. What is your take on this?

A. Overall, this is a true story, but the impact on the trees (mainly hardwood trees) that we use in woodworking is close to zero.

The reason for no impact is that this salinity issue will not go very far upstream in most rivers or very far inland along the coastal regions.

So, very few commercial hardwood trees are nearby these new areas of increased salinity.

It is true that salinity in the soil or water table will affect trees that go to a sawmill.

That is, most commercial timber species are not salt tolerant. In this respect, appreciate that a strong wind blowing on-shore, a strong high tide, and/or decrease of fresh water flowing down a river can result in salinity in the soil.

This will certainly kill most “fresh water” trees, even though the salinity is temporary.

Further, the salt spray on leaves or needles can kill many species, especially softwood trees. (Example is salt spray and salt in the soil of trees near highways treated heavily with salt to melt snow and ice.)

My conclusion as a forester (my degree says “Forestry”) is that drought will damage more hardwoods.

At the same time, flooding will damage these same trees.

Flooding can also damage sawmills, restrict entry into forested lands, which affects log supply, and create a labor shortage due to damage to employees’ family, homes and property. Recent high-rainfall storms that seem to target the central and southern US in the East, along with hurricanes in the Southern and East Coast states, are affecting log supplies and lumber output. A shortage in supply always seems to result in higher lumber prices to our industry.

Have something to say? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.