Managers have long relied on three key financial statements – the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement – to provide the information required to run their businesses. In the early 1990s enlightened companies recognized that these tools reported dated, often difficult-to-interpret information. Managers of today’s complex operations need timelier, easily understood reports describing the performance of the key processes that drive dollars-and-cents outcomes. Equally as important, all employees must know how their efforts can help the company succeed.

That realization led to the development of a new management tool, performance measurement, and its most visible component, the scorecard. Consisting of a carefully selected set of metrics, the scorecard monitors in near-real time the strategic processes and activities that are critical to an operation’s success. While retaining financial metrics like cash flow and revenue growth, today’s typical scorecard includes many non-financial metrics such as first pass quality, on-time delivery, customer satisfaction, and employee retention.

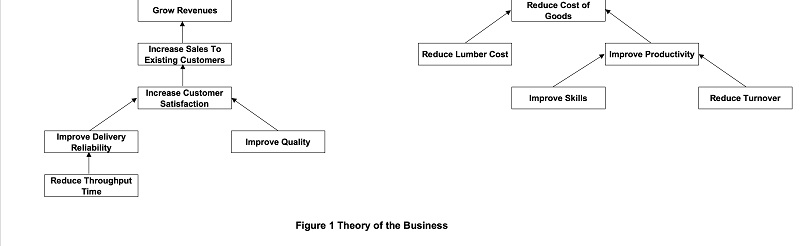

A well-designed scorecard is rooted in the organization’s theory of its business. In the language of sports the theory is the company’s game plan. Its purpose is to answer two key questions:

- What objectives must be reached to achieve strategic success?

- How will those strategic objectives be achieved?

A theory of business can be developed by asking senior management a series of what and how questions and mapping their answers in a flow chart. The exercise begins by answering what is the company’s highest-level strategic objective?

In Figure 1 the answer is improve return on investment. Then ask how will that objective be attained? The answer is twofold: reduce the cost of goods and grow revenues. Following on ask what activities will reduce the cost of goods? The hows in the example are improve productivity and reduce lumber costs. Continuing on ask what activities will improve productivity? The answer is two hows: improve skills and reduce turnover.

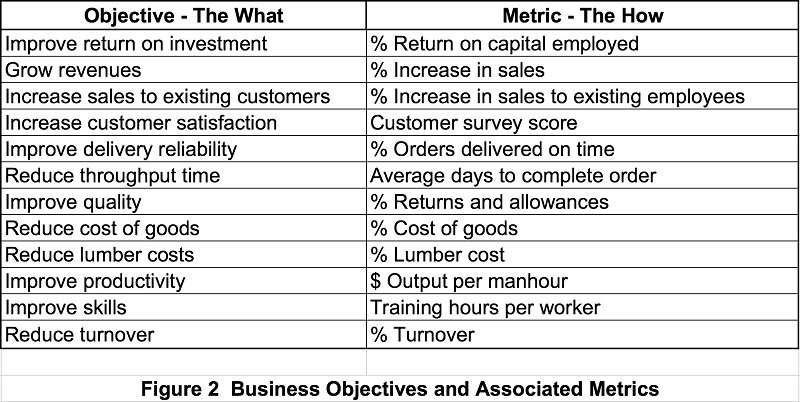

To describe a company’s complete theory of its business, the what-how question-and-answer process resumes until every key objective and activity is listed. In doing so, every strategic process at which the company must excel is defined in clear language. The next step is assigning quantifiable metrics that will track the scores or ratios for each activity. Figure 2 lists the strategic objectives and their metrics for the example.

By highlighting the critical activities, defining acceptable outcomes, and reporting actual performance throughout the organization, a well-designed scorecard can become a company’s core information system. Such a system educates every employee of his responsibilities in clear language and numbers, facilitates better communication, and enables sound decision making.

Building a strategically sound scorecard must be a top-down process. The first step is identifying the business unit for which the scorecard is appropriate. A comprehensive scorecard covers a business wall-to-wall: its financial, customer, people, and process components. Senior executives with their responsibility for setting strategy must be interviewed and updated as the design evolves to cover those components in detail. Their input must include the latest mission statement as well as consensus on the company’s key success factors:

- What financial targets must be met?

- What activities are required to satisfy the customer?

- What processes must be done exceptionally well?

- What people resources must be developed?

With that knowledge in hand, drafts of the theory of business flow chart and a list of suitable metrics can be compiled. Those documents should then be refined to ensure accurate cause-and-effect linkages between the objectives (the whats) and activities (the hows) and to set performance targets. Once that important check is completed, performance targets for each strategic activity and its associated metric can be identified. Responsibility for achieving target performance of every metric must be assigned to a proper job position, and sub-scorecards containing those relevant metrics must be prescribed.

Throughout the design process the company’s information technology staff must be involved to ensure the required data are readily available for input into the scorecard.

Once ready for kick-off, a thorough training program for all users and information providers must be designed and implemented. That effort must be on-going and include discussions of performance with managers and front-line workers and training on problem solving and continuous process improvement.

A well-designed performance measurement system features several characteristics:

- Linkage of cause and effect is critical – If you meet or exceed a performance target without achieving the desired outcome, the theory of business is flawed or your targets are set too low. For example, regularly meeting your on-time delivery target should improve your customer satisfaction score. If not, your customers may not value your performance.

- All metrics must have realistic performance targets – To motivate improvement efforts, moderately challenging stretch targets are recommended.

- Leading or predictor metrics must be included – Leading metrics are forward-looking and often report acceptable performance before an outcome measure does. For example a reduction in returns and allowances for defective products may not immediately impact your customer satisfaction score. Don’t give up on your performance measurement system because the latest news is not yet acceptable.

- Financial and non-financial metrics must be included – Studies show that focus on non-financial measures such as customer satisfaction and employee turnover impact business success.

- Metrics must be actionable – Wherever possible, workers must be able to affect the ratio(s) or score(s) used to judge their performance.

- The scorecard must provide key metrics for the corner office to the plant floor – Key success factors such as revenue growth are often driven by lower-level activity. For example in Figure 1 growth is reached by reducing throughput time, an outcome that results from plant floor initiatives. While scorecard design process is top-down, the scores achieved on high-level metrics are often driven bottom up by front-line workers focusing on set-up time, yield, and feed rates.

- Scorecard reporting must be timely and visible – Especially at a company’s front line, feedback should be fast, even real-time. The longer the time from performance to report the longer the delay in improvement. As importantly, results must be prominently displayed and loudly communicated.

- The scorecard must assign responsibility and accountability for each metric – That ownership should include the support personnel who have the tools and special knowledge for correcting deficient performance.

- The scorecard must be updated annually to reflect the latest strategy and theory of business – Over time a company’s market changes. Different customers may require a new offering of products and services. New process technologies may enable faster delivery times and lower costs.

Bottom Line: A scorecard is all about making the right numbers. Documenting your theory of business, defining your whats and hows, and implementing a scorecard that informs your employees of performance expectations and results will not revolutionize your company overnight. Those tasks will be hard work. But that effort will generate a lasting, company-wide culture focused on the activities that matter to your business, its suppliers, and its customers. Remember Peter Drucker’s advice: “There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

Have something to say? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.